Published in L’Express in May 1957.

Interviewer: A psychoanalyst is very intimidating. One has the feeling that he could manipulate you as he wishes, that he knows more than you about the motives of your actions.

Dr. Lacan: Don’t exaggerate. Do you think that this effect is exclusive to the psycho-analyst? An economist, for many, is as mysterious as an analyst. In our time, it is the expert who intimidates. With psychology, even when seen as a science, everyone thought they had the insider’s track. Now, with psychoanalysis, we have the feeling of having lost that privilege; that the analyst could be capable of seeing something quite secret in what appears to you to be quite clear. There you lie naked, uncovered, under a well-informed eye, and without knowing what you are showing him.

THE OTHER SUBJECT

Interviewer: This is a sort of terrorism. One feels violently torn out from oneself.

Dr. Lacan: Psychoanalysis, in the order of man, has, in fact, all the subversive and scandalous features that the Copernican de-centering had in the cosmic order: the earth, that place inhabited by man, is no longer the center of the universe! Well! Psychoanalysis announces that you are no longer the center of yourself, since there is another subject within you, the Unconscious. It was, at first, not well-accepted news. The so-called irrationalism which has been used to define Freud! When it is exactly the contrary: not only did he rationalize all that had resisted rationalization until he came along, but he even showed that in action there is a process of reasoning going on; I mean, something that is reasoning and functioning logically, without the knowledge of the subject. All of this, viewed classically, as being in the field of the irrational; let’s call it the field of passion.

This is precisely what he was not forgiven for. His introduction of the notion of sexual forces that take over the subject without warning, nor logic, was still admitted; but that sexuality is a place of speech, that neurosis is an illness that speaks, here is something strange, and even his disciples prefer that we speak of something else.

An analyst must not be seen as a “soul engineer”; he’s not a physician, he does not proceed by establishing cause-effect relations; his science is a reading, it’s a reading of sense.

This is why, undoubtedly, without knowing exactly what is hidden behind his office’s door, he is commonly considered as a sorcerer, an even greater one than the others.

Interviewer: And who has discovered these terrible secrets?

Dr. Lacan: It is better to specify the nature of these secrets. They are not the secrets of nature, those discovered by biological and physical sciences. If psychoanalysis clarifies some facts of sexuality, it is not by aiming at them in their own reality, not in biological experience.

ARTICULATED AND DECIPHERABLE

Interviewer: But, Freud, he did discover, in the same way one discovers an unknown continent, a new dimension of psychic life, that is called “unconscious” or something else? Freud is Christopher Columbus!

Dr. Lacan: The knowledge that there is a part of the psychic functions that are out of conscious reach, we did not need to wait for Freud to know this!

If you want a comparison, Freud is instead Champollion! The Freudian experience is not at the level of the organization of instincts and vital forces. The Freudian experience discovers them only by exerting itself, if I may say so, on a secondary force. It is not the instinctual effects in their primary force that Freud deals with. That which is analyzable is so, because it is already articulated in what makes up the singularity of the subject’s history. The subject can recognize himself in it, insofar as psychoanalysis allows the transference of this articulation.

In other words, when the subject “represses”, this does not mean that the subject refuses to gain consciousness of something like an instinct, like, for example, a sexual instinct that would manifest itself in a homosexual form — no, the subject does not refuse his homosexuality, he represses the speech where this homosexuality has the role of a signifier. You see, it is not a vague, dubious thing which is repressed; it is not a sort of need, or tendency, that could have been articulated (and then can’t be articulated because it is repressed); it is a discourse that is already articulated, already formulated in a language. It’s all there.

Interviewer: You say that the subject represses a discourse articulated in a language. Yet, we do not feel ourselves to be there when we’re face to face with a person with psychological difficulties, a timid person, for example, or an obsessional. Their conduct seems absurd, incoherent; and if we guess that it might mean something, this would be imprecise, a faltering tone, sensed at a level lower than the level of language. And oneself, when one feels ridden by obscure forces that we call neurotic, these forces manifest themselves precisely by irrational actions , accompanied by confusion and angst!

Dr. Lacan: Symptoms, those you believe you recognize, seem to you irrational because you take them in an isolated manner, and you want to interpret them directly. For example, take the Egyptian hieroglyphics. As long as we look for the direct meaning of vultures, chickens, the standing, sitting, or moving men, the writing remains indecipherable. When taken by itself, the sign “vulture” means nothing; it only finds its signifying value when taken within the context of the set of the system to which it belongs. Well, analysis deals with this order of phenomena. They belong to the order of language (“langagier” in French).

A psychoanalyst is not an explorer of an unknown continent, or of great depths; he is a linguist. He learns to decipher the writing which is under his eyes, present to the sight of all; however, that writing remains indecipherable if we lack its laws, its key.

REPRESSION OF TRUTH

Interviewer: You say that this writing is “present to the sight of all”. Yet, if Freud has said something new, it was that in psychic life we are ill because we conceal, we hide a part of oneself, we repress. But the hieroglyphics themselves were not repressed, they were written on stone. So your comparison cannot be complete ?

Dr. Lacan: On the contrary, it must be taken literally. What is to be deciphered in psychic analysis is all the time there, present since the beginning. You speak about repression, forgetting something. As Freud formulated it, repression is inseparable from the phenomenon of “the return of the repressed”. Something continues to function, something continues to speak in the place where it was repressed. Thanks to this we can locate the place of repression and of the illness, saying “it is there”.

This notion is difficult to understand because when we speak of repression we imagine immediately a pressure, a vesicular pressure, for example. That is, a vague mass, undefined, exerting all its weight against a door that we refuse to open. Now, in psychoanalysis, repression is not the repression of a thing, it is a repression of a truth. What happens then, when we want to repress a truth? The whole history of tyranny is there to give the answer: It is expressed elsewhere, in another register, in a ciphered, clandestine language. Well, this is exactly what is produced with consciousness.

Truth, the repressed, will persist, though transposed to another language, the neurotic language.

Except that we are no longer capable of saying at that moment who is the subject speaking; but, that “it” speaks, that it continues to speak. It happens that it is entirely decipherable in the manner that we are decipherable, which means, not without difficulty, it’s a lost writing.

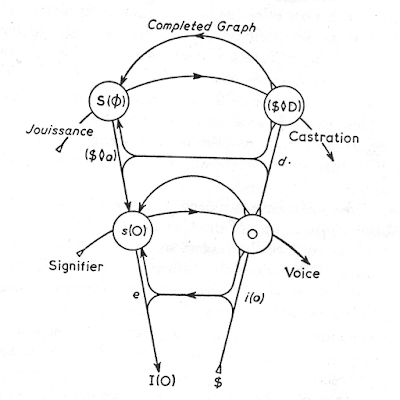

Truth has not been annihilated, it has not fallen into an abyss. It is still there, given, present, but turned into unconscious. The subject who has repressed truth is not the master anymore, he is not at the center of his discourse; things continue to function alone and discourse continues to articulate itself, but “outside the subject.” And this place, this “outside the subject,” is exactly what we call the unconscious.

You can clearly see that what we have lost is not the truth; it is the key to the new language in which it is expressed from then on .

THE HAMMOCK

Interviewer: Isn’t this your own interpretation? It seems that it is not Freud’s?

Dr. Lacan: Read “The Interpretation of Dreams”, read “The Psychopathology of Everyday Life”, read “Jokes and their relation to the Unconscious”. It is enough to open these works, whatever the page, to find clearly what I’m speaking about.

The term “censorship”, for example. Why did Freud choose it straightaway, even at the level of the interpretation of dreams, to designate this restraining insistence, the repressing force? Censorship, as we know, is this anasthasia, this constraint that works using a pair of scissors. And on what? Not on whatever passes by in the air, but rather on what is susceptible of being printed, in a discourse, a discourse expressed in a language.

Yes, the linguistic method is present in every page of Freud’s work; all the time he gives references, analogies, linguistic parallels. And then, in the end, in psychoanalysis, you only ask one thing of the patient, only one thing, that is, to speak. If psychoanalysis exists, and if it has its effects, it is only within the domain of confession and of speech.

Yet, for Freud, as for me, human language does not spring up for human beings like a fountain . Look at the way that, ordinarily, how a child gains experience is represented for us: he sticks his finger on a burning pan, he burns himself. Starting from that moment that he encounters hot and cold, danger, it is maintained that all that remains for him to do is to deduce, to reconstruct all of civilization.

That is absurd. Starting with the fact that he burns himself, he is placed face to face with something which is much more important than the discovery of hot and cold. In fact, he burns himself and then there is always someone who gives him a whole speech about it. Indeed, the child will have a much harder time entering into this linguistic discourse that we have submerged him into, than to learn to avoid the hot pan.

In other words, the man who is born into existence deals first with language; this is a given. He is even caught in it before his birth. Doesn’t he have a civil status? Yes, the child who is to be born is already, from head to toe, caught in this language hammock that receives him and at the same time imprisons him.

CLEARLY, IN EACH CASE

Interviewer: What renders the acceptance of relating neurotic symptoms to a perfectly articulated language difficult is the fact that we don’t see to whom they are addressed. They are not made for anyone, since the ill person, in particular, the ill person, himself, does not understand them, and a specialist is needed to decipher them! Maybe, the hieroglyphics have become incomprehensible, but, at the time they were used, they were made to communicate certain things to certain people. So what is this neurotic language?

It is not only a dead language, it’s not only a private language, since it is incomprehensible to oneself?

And then, a language is something that we use. This one, on the contrary is infringed upon. Take the obsessional. He would certainly like to get rid of his fixed idea, get out of the trap.

Dr. Lacan: These are precisely the paradoxes that are the object of discovery. And yet, if language were not addressed to an Other, it could not be understood thanks to an other in psychoanalysis. The rest is a matter of recognizing what it is, and to do this, it is necessary to situate it in a case; this requires a long time to develop; otherwise it’s a jumble of incomprehension. Nevertheless, it is there, where what I’m talking about can appear clearly: the way the repressed discourse of the unconscious is translated in the register of the symptom. And you can see to what point this is precise. You mentioned the obsessional. Follow Freud’s observation which we find in “The Five Psychoanalyses”, entitled “The Ratman”. The Ratman was a great obsessional. A young man of higher education who finds Freud in Vienna to tell him that he suffers from obsessions. They are sometimes intense worries in relation to his beloved, and sometimes the desire to commit impulsive acts, like cutting his throat, or he constructs for himself interdictions concerning insignificant things.

THE RATMAN

Interviewer: And what about sexuality?

Dr. Lacan: There we find an error of the term! Obsessional does not necessarily mean sexual obsession, not even obsession for this, or for that in particular; to be an obsessional means to find oneself caught in a mechanism, in a trap increasingly demanding and endless. He has to accomplish an act, a duty; a special anxiety takes over the obsessional. Will he be able to accomplish it? Once he has done it, he suffers the torturing need to verify it, but he doesn’t dare because he fears he will appear as a crazy man, because at the same time he knows well he did accomplish it; this commits him to greater and greater cycles of verification, precaution, justification. Taken in this way by an inner whirlwind, it is impossible for him to find a state of tranquillity, of satisfaction. Nevertheless, the great obsessional is far from being delirious. He has no conviction whatsoever, only a kind a necessity, totally ambiguous, that renders him incredibly unhappy, suffering, hopeless, left to an unexplainable insistence that comes from within himself, and that he does not understand.

The obsessional neurotic is common and can go unnoticed, if we are not attentive to the little signs that betray him. The people suffering from this illness occupy their social positions well, even if their life is ravaged, eroded by suffering and by the development of this neurosis. I’ve known people who held important positions, and not only honorary, but positions of leadership, people with great and extended responsibilities, that they assumed completely, but they were not in anyway less caught, all day long, as the prey of their obsessions.

This was the case of the Ratman, distressed, trapped by the return of his symptoms, that lead him to consult Freud in Vienna, where the Ratman was participating in important military exercises as an army reserve official. He asked Freud for advice with regard to a very boring story of a debt he owed to the mail office where he had sent a pair of glasses, a story that he loses track of. If we follow him, literally, right to his doubts, we find in the scenario created by his symptom, a scenario that concerns four persons, the very events that led to the marriage of which the subject was the fruit, trait by trait, transposed into a vast set of mannerisms, without the subject suspecting anything .

Interviewer: What stories?

Dr. Lacan: A fraudulent debt of his father, a military man, grew. The father lost his military rank due to having committed a crime; there was a loan that allowed him to pay his debt, and the unclear aspect of the restitution of the money to the friend who came to his aid, and finally a betrayed love due to a marriage that gave him status.

During his childhood, the Ratman had heard these stories, some light-hearted, others covert.. What is striking is the fact that what returns from the repressed is not a particular event or trauma; it is the dramatic constellation that ruled over his birth, his prehistory.. He is descended from a legendary past. This prehistory reappears via the symptoms that represent that pre-history in an unrecognizable form, that weave it into myth, represented by the subject without awareness. Since it is transposed like a language or a writing, maybe transposed into another language, with other signs; it is rewritten without the modification of the liaisons; like a figure in geometry is transformed from a sphere to a plane, which does not necessarily mean that any figure can transform itself into any other figure.

Interviewer: So, when this story is updated, what comes next?

Dr. Lacan: Listen well…I have not said that the cure of a neurosis is accomplished with this. You know very well that in the cure of the Ratman there is something else that I cannot talk about here. If a prehistory sufficed for the origin of consciousness, everyone would be a neurotic. It is linked to the way the subject assumes things, accepts them or represses them. And why do certain people repress certain things?

Anyway, take the time to read the Ratman using this key that traverses it , part by part; the transposition into another figurative language, totally unperceived by the subject, of something that can only be understood as a discourse.

TO KNOW MORE AND BETTER

Interviewer: It could be that repressed truth is articulated, as you say, in a discourse with ravaging effects. But in the case of someone who comes to you, it is not because he searches for the truth. He is someone who suffers horribly, and wants to be relieved from his pain. If I remember correctly the story of the Ratman, there was also a fantasy of rats.

Dr. Lacan: In other words, while you worry about truth, there’s a man who suffers. In any case, before using an instrument, it’s important to know what it is, how it is manufactured! Psychoanalysis is a terribly efficient instrument, and because it is more and more a prestigious instrument, we run the risk of using it with a purpose for which it was not made for, and in this way we may degrade it.

Therefore it is necessary to depart from the essential: what is it, this technique, what’s its purpose, what are its effects, the effects that it has by its simple and pure application?

Well! The phenomena proper to psychoanalysis are of the order of language. That is, the spoken recognition of the major elements of the subject’s history, a history that has been cut, interrupted, that has fallen onto the underside of discourse. In relation to the effects that we define as belonging to analysis, the analytical effects, as we say — mechanical or electrical effects — the analytical effects are of the nature of the return of the repressed discourse. I can assure you that at the very moment you have put the subject on the couch and you have explained to him the analytical rule as briefly as possible, the subject is already introduced into the dimension of the search for his truth.

Dr. Lacan-And I can assure you, that at the very moment you have put the subject on the couch and even if you have explained to him the analytical rule as briefly as possible, the subject is already introduced into the dimension of the search for his truth.

Yes, just from the fact of having to speak, as he must in front of another, the silence of another – a silence which is neither approving nor disapproving, but rather attentive- he feels it as an expectation, and this expectation is that of the truth.

And also , he feels driven by the prejudice that we had mentioned before:

that of believing that this other, the expert, the analyst, knows something about him that he himself is unaware of; the presence of the truth is fortified, it is there in an implicit state.

The ill person suffers but he realizes that the path to take in order to go beyond, to ameliorate his suffering, is of the order of the truth: to know more and to know better.

–Then, man is a being of language? This would be the new representation of man that we owe to Freud; man is someone who speaks?

Dr. Lacan- Is language the essence of man? This is question which is not of disinterest to me, and I do not detest that people who are interested in what I say are, in fact, interested in this, but it is an interest of a different order, and as I sometimes say, it’s the side event.

I don’t ask myself “who speaks?”; I try to pose the question in a different way, in a more precisely formulated way. I ask “From where does it speak?”

In other words, if I have tried to elaborate something, it is not a metaphysical theory but a theory of intersubjectivity. Since Freud, the center of man is not where we thought it was; one has to go on from there.

–If what counts is to speak, to find one’s own truth through words and confession, would not analysis become a substitute for religious confession?

Dr. Lacan-I am not authorized to talk to you about religious matters, but I must say that confession is a sacrament which is not there to satisfy a certain need for confiding… The response, even if consoling, encouraging, even if directive, of a priest does not pretend to render confession efficient.

–From the point of view of dogma, you are certainly right. However, confession is related, at least for a time which does not cover the entire Christian era, to what is called the direction of conscience.

Would this not be related to the field of psychoanalysis? That is, to make someone confess his actions and intentions, to guide a spirit who searches for his truth?

Dr. Lacan- The direction of conscience has been judged in different manners by spiritual individuals themselves. We have even seen in certain cases, that this can be a source of a variety of abusive practices.

In other terms, it is up to the members of religious orders to determine the place and significance they give to conscience.

But it seems to me that no director of conscience would be alarmed by a technique whose objective is to reveal the truth. I’ve seen how worthy members of religious communities have taken a stand in very delicate affairs, where something that we call family honor was at stake. I have always seen them decide that to keep truth hidden has ravaging consequences.

And, all directors of conscience will tell you that the bane of their existences are obsessional and overly scrupulous persons; they don’t really know how to deal with them: the more they try to calm them down, the worse it gets; the more they try to explain and give them reasons, the more people come to them with absurd questions…

Yet, analytical truth is not as mysterious, or as secret, so as to not allow us to see that people with a talent for directing consciences see truth rise spontaneously.

I’ve known among members of religious orders people who had understood that a penitent who complained about her needs for impurity, needed to be taken to another level: did she behave justly with her children and her maid? And through this brutal reminder, they obtained incredibly surprising effects.

In my opinion, the directors of conscience cannot find fault with psychoanalysis; they can even find in it some useful ideas.

DISTURBING REVERSAL

—Perhaps, but is psychoanalysis well perceived? In the religious domain it would be considered rather a devil’s science.

Dr. Lacan- I think times have changed. Undoubtedly, after Freud invented psychoanalysis, it was considered for a long time as a subversive and scandalous science. It was not about believing in it or not. People were violently opposed to it with the excuse that analyzed persons would be at the mercy of all their raging desires, would do whatever.

As of today, recognized as a science or not, psychoanalysis has entered our habits, and positions have been reversed: when someone does not behave normally, when he is considered as scnadalous in his social circle, we speak of sending him to a psychoanalyst!

All this does not lie in the order of what is called with the too technical term “resistance to psychoanalysis”, but rather “mass objection”.

The fear to lose one’s originality, of being reduced to a common level, is also frequent. One has to say that with the notion of “adaptation” a doctrine of nature has been produced to engender confusion and from there on anxiety.

There has been written that psychoanalysis has as its objective the adaptation of the subject, not precisely to his external environment, his life or his real needs; this means the ratification of an analysis would be to become the perfect father, the model husband, the ideal citizen, in sum, someone who has nothing left to discuss.

All this is completely false. Just as false as the first prejudice that conceives psychoanalysis as a means to total liberation.

—Don’t you think that that which people fear most, that which makes them oppose psychoanalysis even before they consider it a science or not, is the fact that they risk losing a part of themselves, of being modified?

Dr. Lacan- This worry is totally legitimate as it appears. To say that there is no change in the personality after a psychoanalysis would be aé joke. It is difficult to claim at the same time that we can obtain results through psychoanalysis and that we may not obtain them, that is to say, that personality can remain unchanged. In any case, the notion of personality needs to be clarified, or even re-interpreted.

SETTLING (REINSTALLATION) OF THE SUBJECT

–Basically, the difference between psychoanalysis and various psychological techniques is that psychoanalysis is not contented with only guiding, or intervening blindly, psychoanalysis cures…

Dr. Lacan- It cures that which is curable. It will not cure daltonism or idiocy, even if in the end daltonism and idiocy have something to do with the psyche.

Do you know Freud’s formula, “there where it was, I must be” ? The subject must be able to settle in this place, this place where he was no longer, replaced by this anonymous word that we call the “it”.

–In the Freudian perspective, is there an interest in aiming at curing the large number of people who are not ill? In other words, is there an interest in psychoanalyzing everyone ?

Dr. Lacan- To possess an unconscious is not a privilege of neurotics. There are people who are manifestly not overwhelmed by an excessive weight of parasitic suffering, who are not blocked by the presence of another subject-but who would not lose anything if they knew more about him.

Since to be analyzed is nothing different than knowing one’s own history.

–Is this true in the case of creators?

Dr. Lacan- It is an interesting question to know if there is an interest for them to run with or to veil this speech that attacks them from the outside (it’s the same thing as that which blocks the subject in neurosis and in creative inspiration).

Is there an interest in running on the path of psychoanalysis towards the truth of the subject’s history, or to give away, like Goethe, to a great way which is nothing different than an enormous psychoanalysis?

Because in Goethe this is evident: his work is entirely the revelation of the other subject’s speech.

He pushed the thing as far as a genius can do it.

Would he have written something different if he had been analyzed? In my opinion, his work would have been another, but I don’t think it would have been lost.

–And for those men who are not creators but who have enormous responsibilities, who deal with power, do you think that psychoanalysis should be obligatory ?

Dr. Lacan- In fact, we should not doubt that if a man is the President of the council, it is because he was analyzed at a normal age, this means young, but sometimes youth is very long lasting.

SIGNS OF ALARM

–Watch out ! What could one object to Mr. Guy Mollet if he had been analyzed?

If he could have the right to immunization when his contradictors do not?

Dr. Lacan- I wouldn’t take a stand on whether Mr. Guy Mollet would make the politics he makes if he were analyzed! I don’t want to be heard saying that a psychoanalysis applied universally would be the source of the resolution of all antinomies; that if we analyze all human beings, there will not be any more wars, no more class conflicts; formally, I say the opposite. All that we could expect is that human dramas might be less confusing.

Do you see the error in what you were saying awhile ago : wanting to use an instrument without knowing how it is made. Among the activities that are being developed all over the world under the name of psychoanalysis, there is a growing tendency to cover, to fail to recognize, to mask the first order in which Freud brought his spark.

The effort of the great majority of the psychoanalytic schools has been what I call an attempt at reduction: to put in one’s pocket the most disturbing aspect of Freud’s theory. Year after year, we witness the accentuation of this degradation, reaching at times, like in the United States, formulations which are in total contradiction with the Freudian inspiration.

It is not because psychoanalysis is highly contested that analysts should make their observations more acceptable, covering them with multiple colors, and borrowing analogies from neighboring scientific domains.

—This is very discouraging if we think in terms of potential analysands?

Dr. Lacan– If my words disturb you, so much the better. From the point of view of the public, my wish is to emit a sign of alarm, so that there will be, in a scientific field, a very precise requirement concerning the training of analysts.

A TRAINED ANALYST

—Isn’t it already a very long and serious training?

Dr. Lacan- The psychoanalytic teaching, as it is today– medical studies and then a psychoanalysis, a training analysis with a qualified analyst– is lacking something essential, without which I doubt one could consider oneself a well trained analyst: the study of linguistic and historic disciplines, history of religion, etc.

Freud, so as to clarify his thought on training, revives the old term, which I enjoy mentioning, of “universitas literarum”.

Medical studies are evidently insufficient to understand what psychoanalysis says, that is to say, for example, to differentiate in a discourse the meaning of symbols, the presence of myths, or simply to grasp the meaning of what the patient says, just like we grasp the meaning of a text.

At the minimum, for the time being, a serious study of the texts of the Freudian doctrine is rendered possible by the safe haven that is given them by Professor Jean Delay of the faculty of the Clinic of Mental Illness and Encephalitis.

–Do you think that there’s a risk of losing psychoanalysis, as invented by Freud, in the hands of incompetent people?

Dr. Lacan- At present, psychoanalysis is turning more and more to a confusing mythology. We can cite certain signs: erasure of the Oedipus complex, accentuation of pre-oedipal mechanisms, of frustration, substitution of the term anxiety by fear. But this doesn’t mean that Freudism, the first Freudian glow, is not developing all over. We find very clear manifestations of it in all sorts of human sciences.

I’m thinking in particular of what my friend Claude Levi-Strauss told me recently of the tribute paid to the Oedipus complex by ethnographers, by who the Oedipus complex is seen as a profound mythical creation born in our epoch.

It is something very striking and surprising that Sigmund Freud, a man alone, managed to bring out a certain number of effects that had never been isolated before, introducing them into a coordinated network, inventing at the same time a science and a field for its application.

But, in relation to this great work of Freud, which traverses the century like a stroke of fire, our work is lagging behind. I say it with all my conviction. And we will not move ahead until we have enough well trained people to do all that a scientific or technical task requires: after the stroke of genius, an army of workers to harvest the results.

Notes:

Jean François Champollion, 1790-1832, French Egyptologist: deciphered the Rosetta Stone. (Random House Dictionary)

See also

|

| The idea of the

"mirror stage" is an important early component in Lacan’s critical

reinterpretation of the work of Freud. Drawing on work in physiology and

animal psychology, Lacan proposes that human infants pass through a

stage in which an external image of the body (reflected in a mirror, or

represented to the infant through the mother or primary caregiver)

produces a psychic response that gives rise to the mental representation

of an "I". |

~ Lacan For Beginners

~ Free Ebook - The Seminar of Jacques Lacan: The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis

This is the second volume in Brett Kahr’s ‘Interviews with Icons’ series, following on from Tea with Winnicott. Professor Kahr, himself a highly regarded psychoanalyst, turns his attention to the work of the father of psychoanalysis. The book is lavishly illustrated by Alison Bechdel, winner of the MacArthur Foundation ‘Genius’ Award.

This is the second volume in Brett Kahr’s ‘Interviews with Icons’ series, following on from Tea with Winnicott. Professor Kahr, himself a highly regarded psychoanalyst, turns his attention to the work of the father of psychoanalysis. The book is lavishly illustrated by Alison Bechdel, winner of the MacArthur Foundation ‘Genius’ Award.