“The realm of imagination was seen to be a “reservation” made during the painful transition from the pleasure principle to the reality principle in order to provide a substitute for instinctual satisfactions which had to be given up in real life. The artist, like the neurotic, had withdrawn from an unsatisfying reality into this world of imagination; but, unlike the neurotic, he knew how to find a way back from it and once more to get a firm foothold in reality. His creations, works of art, were the imaginary satisfactions of unconscious wishes, just as dreams are; and like them they were in the nature of compromises, since they too were forced to avoid any open conflict with the forces of repression. But they differed from the asocial, narcissistic products of dreaming in that they were calculated to arouse sympathetic interest in other people and were able to evoke and to satisfy the same unconscious wishful impulses in them too.”

― Sigmund Freud, Autobiographical Study, Standard Edition, Vol. XX, pp. 64–65

Showing posts with label Creativity. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Creativity. Show all posts

Art, Creativity, and Psychoanalysis: Perspectives from Analyst-Artists

Art, Creativity, and Psychoanalysis: Perspectives from Analyst-Artists collects personal reflections by therapists who are also professional artists. It explores the relationship between art and analysis through accounts by practitioners who identify themselves as dual-profession artists and analysts. The book illustrates the numerous areas where analysis and art share common characteristics using first-hand, in-depth accounts. These vivid reports from the frontier of art and psychoanalysis shed light on the day-to-day struggle to succeed at both of these demanding professions.

From the beginning of psychoanalysis, many have made comparisons between analysis and art. Recently there has been increasing interest in the relationship between artistic and psychotherapeutic practices. Most important, both professions are viewed as highly creative with spontaneity, improvisation and aesthetic experience seeming to be common to each. However, differences have also been recognized, especially regarding the differing goals of each profession: art leading to the creation of an art work, and psychoanalysis resulting in the increased welfare and happiness of the patient. These issues are addressed head-on in Art, Creativity, and Psychoanalysis: Perspectives from Analyst-Artists.

From the beginning of psychoanalysis, many have made comparisons between analysis and art. Recently there has been increasing interest in the relationship between artistic and psychotherapeutic practices. Most important, both professions are viewed as highly creative with spontaneity, improvisation and aesthetic experience seeming to be common to each. However, differences have also been recognized, especially regarding the differing goals of each profession: art leading to the creation of an art work, and psychoanalysis resulting in the increased welfare and happiness of the patient. These issues are addressed head-on in Art, Creativity, and Psychoanalysis: Perspectives from Analyst-Artists.The chapters consist of personal essays by analyst/artists who are currently working in both professions; each has been trained in and is currently practicing psychoanalysis or psychoanalytic psychotherapy. The goal of the book is to provide the audience with a new understanding of psychoanalytic and psychotherapeutic processes from the perspective of art and artistic creativity. Drawing on artistic material from painting, poetry, choreography, photography, music and literature, the book casts light on what the creative processes in art can add to the psychoanalytic endeavor, and vice versa.

Art, Creativity, and Psychoanalysis: Perspectives from Analyst-Artists will appeal to psychoanalysts and psychoanalytic psychotherapists, theorists of art, academic artists, and anyone interested in the psychology of art.

Art and Mourning: The role of creativity in healing trauma and loss

Buy Art and Mourning here. - Free delivery worldwide

Art and Mourning explores the relationship between creativity and the work of self-mourning in the lives of 20th century artists and thinkers. The role of artistic and creative endeavours is well-known within psychoanalytic circles in helping to heal in the face of personal loss, trauma, and mourning.

In this book, Esther Dreifuss-Kattan, a psychoanalyst, art therapist and artist - analyses the work of major modernist and contemporary artists and thinkers through a psychoanalytic lens. In coming to terms with their own mortality, figures like Albert Einstein, Louise Bourgeois, Paul Klee, Eva Hesse and others were able to access previously unknown reserves of creative energy in their late works, as well as a new healing experience of time outside of the continuous temporality of everyday life.

Dreifuss-Kattan explores what we can learn about using the creative process to face and work through traumatic and painful experiences of loss. Art and Mourning will inspire psychoanalysts and psychotherapists to understand the power of artistic expression in transforming loss and traumas into perseverance, survival and gain.

Art and Mourning offers a new perspective on trauma and will appeal to psychoanalysts and psychotherapists, psychologists, clinical social workers and mental health workers, as well as artists and art historians.

Buy Art and Mourning here. - Free delivery worldwide

Psychoanalysis and the Artistic Endeavor: Conversations with Literary and Visual Artists

Buy Psychoanalysis and the Artistic Endeavor here. - Free delivery worldwide

Psychoanalysis and the Artistic Endeavor offers an intriguing window onto the creative thinking of several well-known and highly creative individuals. Internationally renowned writers, painters, choreographers, and others converse with the author about their work and how it has been informed by their life experience. Creative process frames the discussions, but the topics explored are wide-ranging and the interrelation of the personal and professional development of these artists is what comes to the fore. The conversations are unique in providing insight not only into the art at hand and into the perspective of each artist on his or her own work, but into the mind from which the work springs.

The interviews are lively in a way critical writing by its very nature is not, rendering the ideas all that much more accessible. The transcription of the live interview reveals the kind of reflection censored elsewhere, the interplay of personal experience and creative process that are far more self-consciously shaped in a text written for print. Neither private conversation nor public lecture, neither crafted response (as to the media) nor freely associative discourse (as in the analytic consulting room), these interviews have elements of all. The volume guides the reader toward a deeper psychologically oriented understanding of literary and visual art, and it engages the reader in the honest and often-provocative revelations of a number of fascinating artists who pay testimony to their work in a way no one else can.

This is a unique collection of particular interest for psychoanalysts, scholars, and anyone looking for a deeper understanding of the creative process.

Buy Psychoanalysis and the Artistic Endeavor here. - Free delivery worldwide

Creativity and Psychotic States in Exceptional People: The Work of Murray Jackson

Buy Creativity and Psychotic States in Exceptional People here. - Free delivery worldwide

Creativity and Psychotic States in Exceptional People tells the story of the lives of four exceptionally gifted individuals: Vincent van Gogh, Vaslav Nijinsky, José Saramago and John Nash. Previously unpublished chapters by Murray Jackson are set in a contextual framework by Jeanne Magagna, revealing the wellspring of creativity in the subjects’ emotional experiences and delving into the nature of psychotic states which influence and impede the creative process.

Jackson and Magagna aim to illustrate how psychoanalytic thinking can be relevant to people suffering from psychotic states of mind and provide understanding of the personalities of four exceptionally talented creative individuals. Present in the text are themes of loving and losing, mourning and manic states, creating as a process of repairing a sense of internal damage and the use of creativity to understand or run away from oneself. The book concludes with a glossary of useful psychoanalytic concepts.

Creativity and Psychotic States in Exceptional People will be fascinating reading for psychiatrists, psychotherapists and psychoanalysts, other psychoanalytically informed professionals, students and anyone interested in the relationship between creativity and psychosis.

Psychoanalytic Studies of Creativity, Greed and Fine Art: Making Contact with the Self

Buy Psychoanalytic Studies of Creativity, Greed and Fine Art here. - Free delivery worldwide

Throughout the history of psychoanalysis, the study of creativity and fine art has been a special concern. Psychoanalytic Studies of Creativity, Greed and Fine Art: Making Contact with the Self makes a distinct contribution to the psychoanalytic study of art by focusing attention on the relationship between creativity and greed. This book also focuses attention on factors in the personality that block creativity, and examines the matter of the self and its ability to be present and exist as the essential element in creativity.

Using examples primarily from visual art David Levine explores the subjects of creativity, empathy, interpretation and thinking through a series of case studies of artists, including Robert Irwin, Ad Reinhardt, Susan Burnstine, and Mark Rothko. Psychoanalytic Studies of Creativity, Greed and Fine Art explores the highly ambivalent attitude of artists toward making their presence known, an ambivalence that is evident in their hostility toward interpretation as a way of knowing. This is discussed with special reference to Susan Sontag’s essay on the subject of interpretation.

Psychoanalytic Studies of Creativity, Greed and Fine Art contributes to a long tradition of psychoanalytically influenced writing on creativity including the work of Deri, Kohut, Meltzer, Miller and Winnicott among others. It will be of interest to psychoanalysts, psychoanalytic psychotherapists, historians and theorists of art.

Nietzsche’s 10 Rules for Writers

Between August 8 and August 24 of 1882, Friedrich Nietzsche set down ten stylistic rules of writing in a series of letters to the Russian-born writer, intellectual, and psychoanalyst Lou Andreas-Salomé — One of the First Female Psychoanalysts .

Salomé's mother took her to Rome, Italy when she was 21. At a literary salon in the city, Salomé became acquainted with Paul Rée, an author and compulsive gambler with whom she proposed living in an academic commune. After two months, the two became partners. On 13 May 1882, Rée's friend Friedrich Nietzsche joined the duo. Salomé would later (1894) write a study, Friedrich Nietzsche in seinen Werken, of Nietzsche's personality and philosophy. The three travelled with Salomé's mother through Italy and considered where they would set up their "Winterplan" commune. Arriving in Leipzig, Germany in October, Salomé and Rée separated from Nietzsche after a falling-out between Nietzsche and Salomé, in which Salomé believed that Nietzsche was desperately in love with her.

The list reads:

1. Of prime necessity is life: a style should live.

2. Style should be suited to the specific person with whom you wish to communicate. (The law of mutual relation.)

3. First, one must determine precisely “what-and-what do I wish to say and present,” before you may write. Writing must be mimicry.

4. Since the writer lacks many of the speaker’s means, he must in general have for his model a very expressive kind of presentation of necessity, the written copy will appear much paler.

5. The richness of life reveals itself through a richness of gestures. One must learn to feel everything — the length and retarding of sentences, interpunctuations, the choice of words, the pausing, the sequence of arguments — like gestures.

6. Be careful with periods! Only those people who also have long duration of breath while speaking are entitled to periods. With most people, the period is a matter of affectation.

7. Style ought to prove that one believes in an idea; not only that one thinks it but also feels it.

8. The more abstract a truth which one wishes to teach, the more one must first entice the senses.

9. Strategy on the part of the good writer of prose consists of choosing his means for stepping close to poetry but never stepping into it.

10. It is not good manners or clever to deprive one’s reader of the most obvious objections. It is very good manners and very clever to leave it to one’s reader alone to pronounce the ultimate quintessence of our wisdom.

Beneath the list, Andreas-Salomé reflects on Nietzsche’s style in light of his aphoristic predilection:

“To examine Nietzsche’s style for causes and conditions means far more than examining the mere form in which his ideas are expressed; rather, it means that we can listen to his inner soundings. [His style] came about through the willing, enthusiastic, self-sacrificing, and lavish expenditure of great artistic talents … and an attempt to render knowledge through individual nuancing, reflective of the excitations of a soul in upheaval. Like a gold ring, each aphorism tightly encircles thought and emotion. Nietzsche created, so to speak, a new style in philosophical writing, which up until then was couched in academic tones or in effusive poetry: he created a personalized style; Nietzsche not only mastered language but also transcended its inadequacies. What had been mute, achieved great resonance.”

The list comes from the book “Nietzsche” written by Salomé long after their friendship had ended. It provides a retrospective of Nietzsche’s life and philosophical career. (Nietzsche by Lou Andreas-Salomé)

See also:

Daily Rituals: How Artists Work

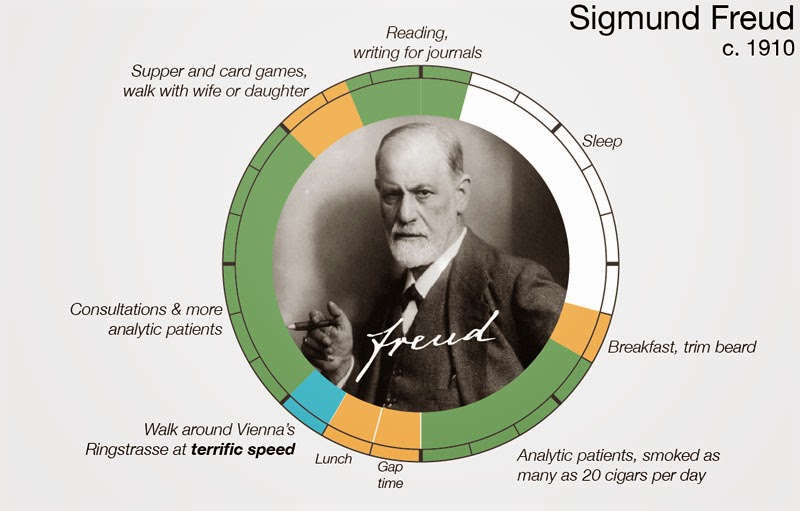

Anthony Trollope wrote three thousand words every morning before heading off to his job at the Post Office. Toulouse-Lautrec did his best work at night, sometimes even setting up his easel in brothels, and George Gershwin composed at the piano in pyjamas and a bathrobe. Freud worked sixteen hours a day, but Gertrude Stein could never write for more than thirty minutes, and F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote in gin-fuelled bursts - he believed alcohol was essential to his creative process.

From Marx to Murakami and Beethoven to Bacon, Daily Rituals examines the working routines of more than a hundred and sixty of the greatest philosophers, writers, composers and artists ever to have lived. Filled with fascinating insights on the mechanics of genius and entertaining stories of the personalities behind it, Daily Rituals is irresistibly addictive, and utterly inspiring.

See also

Daily Routines of History's Greatest Creative Minds [infographic]

Using the book Daily Rituals: How Artists Work by Mason Currey, RJ Andrews at Info We Trust designed some enlightening visualizations of how history’s most creative and influential figures structured their days.

Buy Daily Rituals: How Artists Work here. - Free delivery worldwide

- Gustave Flaubert,

- Ludwig Van Beethoven

- W.A. Mozart

- Thomas Mann

- Sigmund Freud

- Immanuel Kant

- Maya Angelou

- John Milton

- Honore de Balzac

- Victor Hugo

- Charles Dickens

- W.H. Auden

- Charles Darwin

- P.I. Tchaikovsky

- Le Corbusier

- Benjamin Franklin

|

| Click on the graphic for a bigger version |

Data are from Mason Currey’s book Daily Rituals: How Artists Work:

Buy Daily Rituals: How Artists Work here. - Free delivery worldwide

Franz Kafka, frustrated with his living quarters and day job, wrote in a letter to Felice Bauer in 1912, “time is short, my strength is limited, the office is a horror, the apartment is noisy, and if a pleasant, straightforward life is not possible then one must try to wriggle through by subtle maneuvers.”

Kafka is one of 161 inspired—and inspiring—minds, among them, novelists, poets, playwrights, painters, philosophers, scientists, and mathematicians, who describe how they subtly maneuver the many (self-inflicted) obstacles and (self-imposed) daily rituals to get done the work they love to do, whether by waking early or staying up late; whether by self-medicating with doughnuts or bathing, drinking vast quantities of coffee, or taking long daily walks. Thomas Wolfe wrote standing up in the kitchen, the top of the refrigerator as his desk, dreamily fondling his “male configurations”. . . Jean-Paul Sartre chewed on Corydrane tablets (a mix of amphetamine and aspirin), ingesting ten times the recommended dose each day . . . Descartes liked to linger in bed, his mind wandering in sleep through woods, gardens, and enchanted palaces where he experienced “every pleasure imaginable.”

Here are: Anthony Trollope, who demanded of himself that each morning he write three thousand words (250 words every fifteen minutes for three hours) before going off to his job at the postal service, which he kept for thirty-three years during the writing of more than two dozen books . . . Karl Marx . . . Woody Allen . . . Agatha Christie . . . George Balanchine, who did most of his work while ironing . . . Leo Tolstoy . . . Charles Dickens . . . Pablo Picasso . . . George Gershwin, who, said his brother Ira, worked for twelve hours a day from late morning to midnight, composing at the piano in pajamas, bathrobe, and slippers . . .

Here also are the daily rituals of Charles Darwin, Andy Warhol, John Updike, Twyla Tharp, Benjamin Franklin, William Faulkner, Jane Austen, Anne Rice, and Igor Stravinsky (he was never able to compose unless he was sure no one could hear him and, when blocked, stood on his head to “clear the brain”).

Brilliantly compiled and edited, and filled with detail and anecdote, Daily Rituals is irresistible, addictive, magically inspiring.

•

Sigmund Freud on Creative Writing

“The opposite of play is not what is serious but what is real.”

Should we not look for the first traces of imaginative activity as early as in childhood? The child’s best-loved and most intense occupation is with his play or games. Might we not say that every child at play behaves like a creative writer, in that he creates a world of his own, or, rather, rearranges the things of his world in a new way which pleases him? It would be wrong to think he does not take that world seriously; on the contrary, he takes his play very seriously and he expends large amounts of emotion on it. The opposite of play is not what is serious but what is real. In spite of all the emotion with which he cathects his world of play, the child distinguishes it quite well from reality; and he likes to link his imagined objects and situations to the tangible and visible things of the real world. This linking is all that differentiates the child’s ‘play’ from ‘phantasying.’

The creative writer does the same as the child at play. He creates a world of phantasy which he takes very seriously — that is, which he invests with large amounts of emotion — while separating it sharply from reality.

The relation of phantasy to time is in general very important. We may say that it hovers, as it ware, between three times — the three moments of time which our ideation involves. Mental work is linked to some current impression, some provoking occasion in the present which has been able to arouse one of the subject’s major wishes. From here it harks back to a memory of an earlier experience (usually an infantile one) in which this wish was fulfilled; and now it creates a situation relating to the future which represents the fulfillment of the wish. What it thus creates is a day-dream or phantasy, which carries about it traces of its origin from the occasion which provoked it and from the memory. Thus, past, present and future are strung together, as it were, on the thread of the wish that runs through them.

How the writer accomplishes this is his innermost secret; the essential ars poetica lies in the technique of overcoming the feeling of repulsion in us which is undoubtedly connected with the barriers that rise between each single ego and the others. We can guess two of the methods used by this technique. The writer softens the character of his egoistic day-dreams by altering and disguising it, and he bribes us by the purely formal — that is, aesthetic — yield of pleasure which he offers us in the presentation of his phantasies. We give the name of an incentive bonus, or a fore-pleasure, to a yield of pleasure such as this, which is offered to us so as to make possible the release of still greater pleasure arising from deeper psychical sources. In my opinion, all the aesthetic pleasure which a creative writer affords us has the character of a fore-pleasure of this kind, and our actual enjoyment of an imaginative work proceeds from a liberation of tensions in our minds. It may even be that not a little of this effect is due to the writer’s enabling us thenceforward to enjoy our own day-dreams without self-reproach or shame.

"The first single-volume work to capture Freud's ideas as scientist, humanist, physician, and philosopher."

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

|

| Bartleby, the Scrivener: “I would prefer not to.” |